No going upstairs for the hobbit… (The Hobbit, p.1)

Tolkien has become a monster, devoured by his own popularity and absorbed into the absurdity of our time… The chasm between the beauty and seriousness of the work, and what it has become, has overwhelmed me. The commercialization has reduced the aesthetic and philosophical impact of the creation to nothing. There is only one solution for me: to turn my head away. (Christopher Tolkien, Le Monde, 2012)

Softly Sam began to climb. He came to the guttering torch, fixed above a door on his left that faced a window-slit looking out westward… Quickly Sam passed the door and hurried on… He came next to a window looking east… (LotR, VI, i)

Foreword to the Modern Edition

A Hobbit’s Guide to Stairs was composed in Undertowers around the year 953 of the Fourth Age, a local Hobbit response to catastrophic events in Hobbiton nearly two decades earlier.

The Guide was designed to be used as a Tower. The Hobbit reader begins on the ground and ascends several turns of a staircase to reach the first floor, and then up and on, all the way to the top of the tower – whereupon one can turn around, look down, and see the point of stairs.

The original ascension of the staircase was by ‘steps’, that is, Wednesday installments posted on the door of the tallest of the three towers of the now ancient colony. Eventually these posts were gathered in a bound volume and housed next to the prized Undertowers Red Book (actually a copy of a copy, but the Hobbits of Undertowers liked to think of it as the original Red Book of the Westmarch, deposited by the last of the Ringbearers).1

This first modern adaptation of the ancient Hobbit Guide is not a scholarly edition. While the Undertowers Hobbits on the whole retained their traditional good sense and taste, the discovery of the early manuscripts of the Red Book (on which more below) fostered some peculiar literary theories about authorship (which usually ended up in the House of Tom Bombadil) and a queer metaphysics of burglary. Such passages are verbose and tedious in the extreme and make weary reading today for all but dedicated scholars. Our editorial policy has been to translate the Guide into a modern English that reflects its original spirt, while passing over all passages in which the Hobbit authors engage in one or more of the following:

- genealogies

- speculative fantasies woven around the ins and outs of burglarly in holes and houses (especially those invoking the mark of the mushroom)

- quote their own attempts at ‘Elvish poetry’ (invariably abysmal and beside the point).

This modern edition of the Guide contains the same number of floors and steps (posts) as the orignal but, unlike the original, will not cause permanent damage if it falls on your foot.

Our editorial goal has been to meet the urgent need for clarity on stairs in our online and virtual Middle-earth. We humbly suggest that beneath the endless genealogies, outrageous allegories of burglary, and bad poetry, the authors of A Hobbit’s Guide to Stars have something to teach us today. Nevertheless, in an age such as our own that has once again forgotten the meaning of stairs, it is no doubt helpful to recall some of the tragic family history that stands in the background of the Guide before approaching its steps.

Art credit: Drifa, with use of ‘Bilbo the Hobbit’ by AubreesPassions On Deviant Art

Table of Contents

Prologue: On Folly

History repeats itself. First as tragedy, then as farce. (Karl Marx)

Folly

Lack of good sense, foolishness: “an act of sheer folly”

A costly ornamental building with no practical purpose, especially a tower or mock-Gothic ruin built at the top of the Hill

The Shire in the tenth century of the Fourth Age was much changed from its rustic condition at the end of the Third Age. Hobbits had grown more than comfortable, what with the new trade routes that flowed south and east and the river-empires carved out ‘absent-mindedly’ in the far south and east of Middle-earth. With new wealth flowing in, entrenched respectability was inexorably bloated by ostentatious fashion, which lavishly exceeded the bounds of all sense and proportion. The Hobbits of the flatlands of the Marish, for example, raised great artificial mounds around their old houses to make mock holes. But in the far West, by the Hills near the Sea of the colony of Undertowers, the Glastonbury of this age of the world, one pocket of Hobbits continued to tend their mushrooms and to tell each other decent stories. Turning their backs on the vulgar tide of wealth and fashion, they turned their faces to the sea.

The Hobbits of Undertowers had never burrowed holes. A hobbit-hole is burrowed into the upper parts of a hill, and in their vicinity the tops of the Hills were already occupied by three extremely ancient Elf-towers. The Hobbits dwelled in houses at the bottom of the Tower Hills. As time passed, their numbers were slowly swelled by eccentric outcasts from other regions of the Shire, who resented the oppressive respectability of a decadent fashion and romanticized the ancient Elvish poetry that was still venerated in those days in Undertowers. The Hobbits of Undertowers were inordinately proud of their towers, and it was a proverb among them that a Hill is to build, not to burrow.

By some chance confluence of circumstances, the radical spirit of Undertowers entered into the heart of Hobbiton in the year 921. Hobbits, of course, preface the tale with elaborate genealogies, which in those days they liked to believe stretched unbroken all the way back to at least the middle of the Third Age (following the absurd fashion for name-changing of the 640s, the family names of these days had usually only accidental connection with those recorded in the Red Book). But we may begin in 899 when a young Adamanta Chubb was the tempestuous heiress of Bag-end, the luxurious hole at the top of the Hobbiton Hill.

Adamanta, who had always been strong-willed, caused a stir when she had a passionate affair with the Bag-end gardener, conceived a love child, but refused to become Mrs. Bag-end Gardener. Some months after her confinement in one of the cellars, Adamanta escaped down the Hill and fled into the West with Albusbalbus, her baby son. Adamanta raised Albusbalbus in Undertowers, where they had many distant relatives, and where she eventually became head librarian of the famous library. Meanwhile, young Albus, as everyone called him, grew like a weed, scampering all day up and down the Hills with his cousins and even taking the long walk west, to see the sea. When he hit his tweens, Albus would sit with his friends and tween relations at the foot of one or other of the unworldly towers at the tops of the Hills, reading aloud to one another their latest attempts at Elvish poetry, blowing smoke-rings, and otherwise chasing the wonders of pipeweed. But when he walked alone, Albus thought about his unknown father, the gardener at Bag-end who had tended the great tree on the top of the Hill. The tree underneath which Albus was born, but the leaves of which he had never seen in waking life.

Then one Tuesday in the year 921 of the Fourth Age, Adamanta’s dowager mother died. The Bag-end gardener was now manager of a tea-plantation in Far Harad, and so Adamanta declined the inheritance, which therefore passed to Albus, along with the famed wealth of the legendary cellars of the celebrated hole at the top of the Hill. Adamanta could not forgive her son for going ‘up Hill’, as she put it, and never visited him in Hobbiton. But while he was sorry to upset his mother, Albus had long hankered after a hole of his own. And though he felt only emptiness when he first beheld the tree at the top of the Hill, and never quite felt comfortable under its shadow, he soon found that he enjoyed the bachelor life of Bag-end. Albus was now so wealthy that the hyper-respectable Hobbiton Hobbits overlooked practically all his Undertowers oddities. Strangely-bearded folk would wander up the road to the Hill at all hours of the day, and Albus hosted parties long into the night, when the sound of strange music would float out over the garden, down through the meadows, and into the windows of the houses by the river. But so long as he maintained the custom of hosting a great birthday party once a year under the tree at the top of the Hill, with presents distributed to all and sundry, nobody complained too much.

Albus came into his inheritance already lost in strange dreams of his own making. In his imagination he now assumed the role of the Gardener of Bag-end. But he rarely went into the garden. Though he never knew it, his father was a Baggins, and in his own heart Albus wished only to burrow a hole of his own. But he had been nurtured in the spirit of adventure by his mother and cousins in Undertowers, and his head was full of old stones and confused visions of Elvish stairs. His new wealth and the craven counsels of his Hobbiton neighbors helped the situation not one jot. And of course, in those disenchanted days the wizards had all passed back over the Sea, along with the Stone and the three Rings of the Elves under the Sky. So nobody came up the Hill one Tuesday to point poor Albus in the right direction. Left to his own devices, Albus sat at his desk composing Elvish poetry until, one premature Monday morning, he put two and two together and made five.

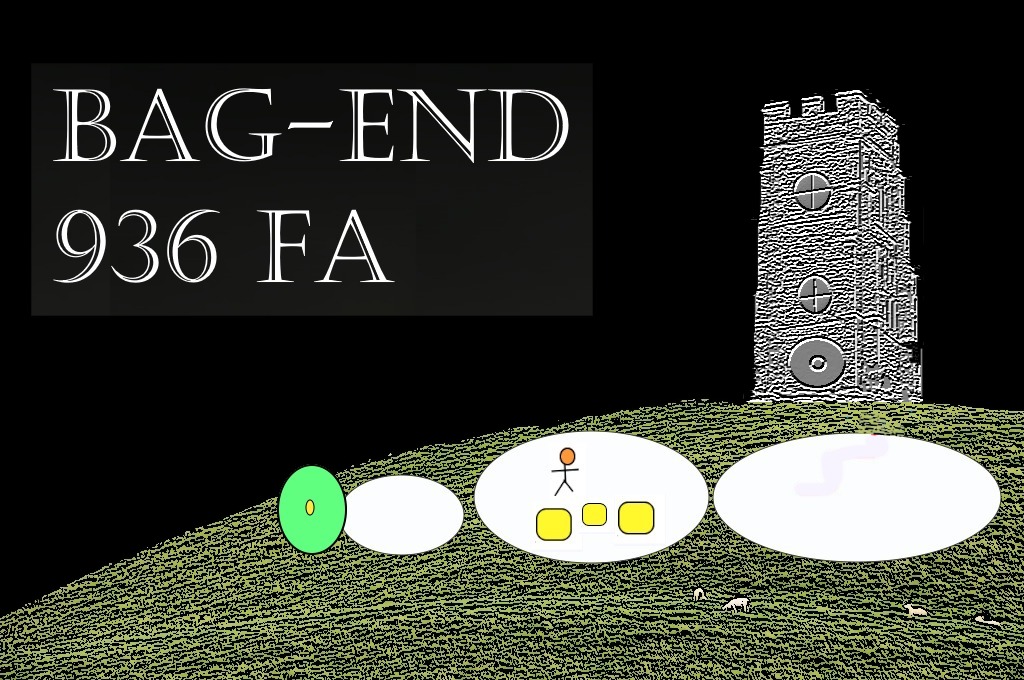

On that Monday afternoon, it was early in the new year 936, Albusbalbus Chubb, master of Bag-end, called on the Hobbits who worked his garden and expressed his wish that they cut down the ancient tree on the top of the Hill. Where the tree had stood, Albus built a mock Elvish tower.

We are still living today with the catastrophic consequences of Albus Chubb’s calamitous error of judgment.

A Hobbit’s Guide to Stairs was the considered response to this tragedy by the Undertowers Hobbits. With grim determination, they set out to sort out, once and for all, what stairs have to do with Hobbits and what Hobbits have to do with stairs. Driven in their antiquarian research by a collective resolve that no Hobbit would ever again realize the fantasy of the Great Folly on the Hobbiton Hill.

In our own troubled days we have much to learn from the Hobbits of Fourth-Age Undertowers.

The Hobbits of Undertowers were in a privileged position to undertake their great venture. Some generations after the last Ringbearer had departed over the Sea, one of his descendants had a clear-out at Bag-end, the result of which was the donation of a cart-load of manuscripts to the Undertowers library. Piled in a heap in a corner of the library stacks for time out of mind, the donation was rediscovered by Adamanta Chubb. Adamanta’s famous catalogue of the Undertowers archive was the foundation of the antiquarian scholarship on which the Guide to Stairs was built. And the foundation of the Guide was the large bundle of early draft manuscripts left by the Bag-end authors of the Red Book.

To facilitate modern use of the Guide, Adamanta’s archaic classification system has been replaced with the canonical references of today, while comments, interpolations, and modern dates, are inserted here and there throughout the Guide, usually in parentheses or footnotes, but not always (because it takes a lot of work to do this properly and it is not paid very well). As noted, the various speculative theories as to the metaphysical significance of these early drafts of the canonical story of the War of the Ring have been cut from this popular edition, but it should be remembered that the individual authors of the various steps of the Guide held divergent and often contradictory positions on the ‘authorship’ question. In those more gentle days, of course, the divisions and oppositions had not become the bitter sectarian battles of later ages, and the word ‘heresy’ had never yet been uttered by a Hobbit of the Shire.

The Wednesday posts were anonymous, and much scholarly ink has been spilled on a quixotic quest to name the three distinct Hobbit-hands that most scholars agree fashioned the majority of the steps. What is certain is that the effort was overseen by the stern eye and whip-hand of Adamanta Chubb, who was evidently the artistic spirit behind the collective enterprise. Adamanta reproached herself for what Albus had done to the great tree. Had she been less stiff-necked, and so on hand to offer her wise counsel, she believed that Albus might have been saved from his tremendous folly. The truth of the matter, however, is that Albus had long ago concluded that his mother had lost her marbles and, having inherited her stiff neck, would very likely have cut down the tree whatever Adamanta had said. But those interested in such biographical tangles, as too Adamanta’s inexplicable final climb and disappearance into the Old Forest and subsequent iconization by the Undertowers mushroom artists of the next generation, should consult the Book of the Unlockable Lock, presently in the hands of the Dwarves.

Notes

1 Whilst this modern edition of the Fourth Age Guide was being put together, the photocopied pages accidentally fell on the floor and it is possible that the order given below is not in every way true to the original.

On the Doorstep: Three Stairless Hobbits

Wednesday 1: Gollum

The Guide does not turn away from a staircase, yet neither does it contribute to baseless prejudice. Three stairless Hobbits frame a first sober perspective on stairs. Today, Gollum.

Gollum is the original fallen Hobbit. No stair is mentioned in the story of his fall, and this because his is a stairless story. Gollum’s fall involves a birthday, a best friend (deceased), water and a boat, a fish, kicking, biting, burrowing like a maggot, and countless years living in a nasty wet hole at the end of a sloping but stairless goblin tunnel.

Conclusion: The One Ring has nothing to do with Stairs.

Wednesday 2: Ted Sandyman

The Sandymans work the Mill pictured at the bottom of ‘The Hill,’ the nearest you will see to a tower in Third-Age Hobbiton! Like Gaffer Gamgee, Ted’s father drinks in The Ivy Bush. Ted frequents The Green Dragon, as does the Gaffer’s son, Sam. The Gamgees and the Sandymans do not seem to like each other, but they are peers among Hobbits. The Mill may have stairs, but the millers down by the Water are no less respectable than the gardeners up Hill down below Bag-end.

Ted’s father was a Hobbit with stairs, but Ted does not have stairs.

Ted reappears at the end of the tale. Back in Hobbiton, our four heroes arrive at the Water and look up the Hill upon a scene of desolation: the party tree has been cut down, Bagshot Row dug up, wanton destruction is everywhere. But the Mill has been rebuilt - larger than before, it now straddles the Water.

There was a surly hobbit lounging over the low wall of the mill-yard. He was grimyfaced and black-handed. ‘Don’t ’ee like it, Sam?’ he sneered. ‘But you always was soft. I thought you’d gone off in one o’ them ships you used to prattle about, sailing, sailing. What d’you want to come back for? We’ve work to do in the Shire now.’ (LotR VI, viii)

Presumably the new Mill has even more stairs than did the old. But they are not Ted’s stairs. They belong to Lotho Sackville-Baggins, aka Pimple, who knocked the old Mill down almost as soon as he took over Bag-end at the top of the Hill. As Farmer Cotton explains, he then built a bigger one, “full o’ wheels and outlandish contraptions”:

Only that fool Ted was pleased by that, and he works there cleaning wheels for the Men, where his dad was the Miller and his own master. (LotR VI, viii)

Convoluted conclusion: Cleaning stairs is no fun. If you must do so, better by far to clean your own than the stairs of Pimple, the Sackville-Baggins who lives with his mother in the luxurious stairless-hole at the top of the Hill.

Wednesday 3: Peregrin Took

‘Short cuts make long delays’ says the Hobbit who will take the ultimate Third-Age shortcut. The horizontal-cut that he questions leads to an encounter with a company of Elves who sing of Elbereth as they travel East from the Tower Hills. The vertical-cut that he makes dispenses with 3,000 years of Númenórean convention and does not lead to a vision of Elbereth over the sea, clear but remote, nor even to a vision like those of Frodo Baggins, who perceives, with an ever-keener eye, the Eye in the Dark Tower.

Peregrin Took looks into the eyes of Sauron.

Gollum is the only other Hobbit to enjoy an interview with Sauron, and he walked all the way to Mordor to do so. Pippin joins an exalted company of old men who see eye to eye with Sauron without going to Mordor: Saruman, Denethor, and Aragorn (Gandalf resists the call). These face-to-face communications occur silently, mediated by two aligned Elvish crystal balls: Palantíri, or Seeing Stones.

The king who returns strives for mastery with Sauron from a high chamber within the Hornburg, a lofty tower now in Rohan but built by the sea-kings of old. Aragorn reclaims his own – the Stones are heirlooms of the house of Elendil. The wizard in Orthanc and the Steward in the white tower both fall. Denethor is the more noble, his end in heathen despair the more terrible – he had a right to use the Stone in the white tower, though it was folly to challenge the will of Sauron. Saruman is greedy and foolish and, caught by the eyes in the Ithil Stone, turns traitor. Saruman’s staff is broken by Gandalf and, almost immediately, the instrument of his undoing is hurled from a high chamber above: a crystal ball narrowly misses both wizards and cracks the external stairway of Orthanc – more than the Ents had achieved!

Pippin, who retrieves the Stone and takes it back into his own hands that night on the ground, is saved from gifting knowledge of Frodo and the One Ring to the Enemy only because Sauron in his malice has not the whit to see that the Orthanc Stone is no longer in a high chamber in the Tower of Orthanc.

Pippin’s shortcut is Sauron’s folly. In the days of Elendil the Men of the West set seven Stones in seven Towers – each apparently in high chambers at the very top of these towers. We cannot account for the position within their towers of all the Stones, but Orthanc suggests a high location in the tower, and the tale of Denethor points to the very highest chamber. As a working assumption, we infer that, by convention, the Númenóreans placed each of the seven Stones at the very top of each of the seven towers, so that one who would look into a Palantír must first ascend a (presumably spiral) staircase all the way to its end (and possibly beyond, by ladder).

Of these seven towers, the earliest erected was the tallest of our three Elf-towers, where Elendil placed his singular Stone. Any Elves subsequently looking into Elendil’s Stone on the Tower Hills would surely have continued this Númenórean ritual of housing the Stone in a high chamber. How they ascended to this chamber is a mystery to us of the Fourth Age of the world. But this Elvish far-seeing into the West of the later Third Age is unusual in that only this Elvish Stone was housed in an Elvish Tower. All other six stones were housed in Númenórean towers and assuredly viewed by prior ascent of a staircase built by the Men of the West.

And then the Hobbit Peregrin Took steps into the picture and, with arguably the most reckless shortcut in the history of Middle-earth, demonstrates that all this stair-ritual is just convention – one can take the Stone down the stairs, even take it away from the Tower, and use it on the ground – and it still works!

Preliminary Conclusion: You can achieve the same ends without stairs – but be more than usually careful if you try this at home.

Staircase to First Floor: Both Sides of the Hill

First Turn: The Red Book

Wednesday 1: Some Hobbits Have Stairs

Hobbits do not like heights, and do not sleep upstairs, even when they have any stairs. (LotR II, vi)

Facing a night in an Elvish treehouse (flet), four Hobbits are naturally unhappy. Yet the narrator suggests that some Hobbits do have stairs. Which Hobbits have stairs?

There is no mention of stairs in the Shire in the whole of The Lord of the Rings. The noun first appears in the house of Tom Bombadil, who is heard going up and down his own. The last usage is ‘Many Partings,’ when Celeborn and Galadriel head off home via the Dimrill Stair.

We read of stairs aplenty outside the Shire. The Dimrill Stair is first encountered as the path over the Mountains, while the Mines of Moria under the Mountains are full of “endlessly branching stairs” and a lost (and destroyed) Endless Stair. In Lothlórien, it is the wish of Galadriel that the Company ascend many stairs so that she can read their minds high up in a tree. Rohan has its stairs, Minas Tirith has even more, and Orthanc is all stairs: Gandalf is imprisoned on the pinnacle of the tower, the only descent “a narrow stair of many thousand steps”; to master the voice of Saruman, Théoden first ascends 27 black stone steps from the foot of the tower – stairs that crack and splinter when Wormtongue hurls down a Palantír. And of course, the way into Mordor requires two heroic Hobbits to follow their treacherous guide up the Stairs of Cirith Ungol.

‘Yes, yess, longer,’ said Gollum. ‘But not so difficult. Hobbits have climbed the Straight Stair. Next comes the Winding Stair.’ (LotR VI, viii)

The wide world beyond the Shire is full of stairs, and Hobbits who adventure within it will sooner or later confront a staircase. The ideal that we have of the Hobbits in their native Shire in the late Third Age is a vision of peace and plenty and well-tilled land - and no stairs. Yet this author of the Red Book suggests that some Hobbits have some stairs.

Who are these Hobbits?

Wednesday 2: Geography

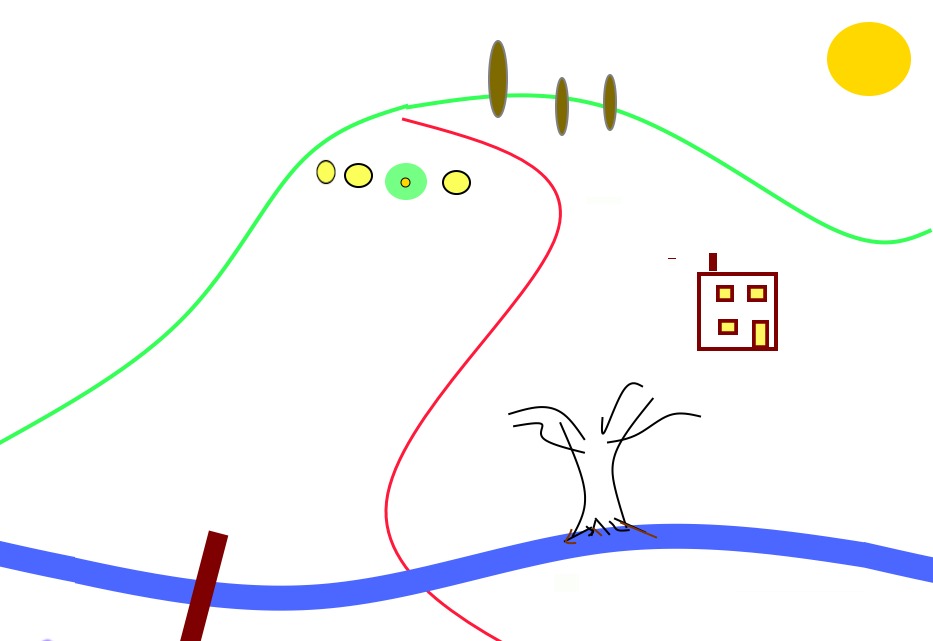

A Hobbit-hole requires a hill. The picture of the Hill of Hobbiton shows that Hobbits who live on flat land build houses, which may have more than one floor and, therefore, employ the device of stairs.

The Hobbits of Undertowers have asked the Librarian how many flights of stairs are suggested in The Hill? Adamanta has passed on the question to me.

The answer of Tobias Took, Undertowers scribe: The Hill suggests three flights of stairs: the Old Grange, the granary on the left going up the Hill, which includes second-floor windows, and the Mill, the three stories of which almost make it a Hobbit Tower. But I keep thinking I am counting wrong.1

1 Editorial note: This question, tentatively addressed by an almost anonymous Hobbit of the Fourth Age, still awaits a definitive answer.

Wednesday 3: Dwarvish Devices

The original travel memoir of Bilbo Baggins suggests that no Hobbits have stairs, but the illustration of The Hill, wherein at the top is his hole, reveals the memoir as the perspective of a top-of-the-Hill dweller who never notices the stairs of his own valley.

Stairs are mentioned in The Hobbit (1937) on precisely seven occasions, the first in the second paragraph:

No going upstairs for the hobbit… (p.1)

But we must cross the Wild and then the Hall of Thrain before an actual stair is glimpsed, though they then come thick and fast:

They climbed long stairs and turned and went down wide echoing ways, and turned again and climbed yet more stairs, and yet more stairs again. (p. 247)

More stairs on the way to and from Ravenhill. The seventh and final is a homesick Hobbit (intending to sneak out with the Arkenstone):

I am tired of stairs and stone passages. I would give a good deal for the feel of grass at my toes. (p. 2474)

One would think from this Hobbit’s travel memoir that stairs are found only on the other side of the Wild. But the illustration that accompanies the great tale of his adventure reveals that some Hobbits have stairs.

Wednesday 4: Architecture

Nothing about a hole forbids stairs.

Bag-end has a door-step, a sort of external singular stair, alone, itself, and nameless. Do not forget this humble door-step, which may prove an internal stair just waiting for the chance to come out.

But the bottom line is that the difference between Dwarves and Hobbits concerns more than just beards - Dwarves know how to do stairs in a hole. Hobbit holes under a Hill are as stairless as Goblin holes under the Mountains. But Goblins tunnel at an incline, and so move up and down underground without the Dwarvish device of stairs. Hobbits simply do not go up and down within their holes, which are all on one horizontal level. Let’s return to the second paragraph of the original adventure.

The door opened on to a tube-shaped hall like a tunnel… The tunnel wound on and on, going fairly but not quite straight into the side of the hill… No going upstairs for the hobbit: bedrooms, bathrooms, cellars, pantries (lots of these), wardrobes (he had whole rooms devoted to clothes), kitchens, dining-rooms, all were on the same floor, and indeed on the same passage. The best rooms were all on the lefthand side (going in), for these were the only ones to have windows, deep-set round windows looking over his garden, and meadows beyond, sloping down to the river.

This long corridor is the backbone of Hobbit architecture, the art of making a horizontal hole in the side of a Hill. The passage or corridor into the Hill makes the magic of a horizontal hole, in which a cellar door leads into a room that is at once deeper underground and on the same level as the living room.1

1 Editorial note. Unfortunately, this art was lost in the celebrated reconstruction of Bag-end in the early 21st-century movies of our own age of the world. Hence we now have a generation of fanatical readers who have never seen what this second paragraph spells out, whose foundational image of Bag-end is of rooms opening onto rooms.

The vanishing of the long passage is the bitter burying of the burrow, an evaporation of Hobbit sense that today falls back on our heads as a hard rain on a doomed forest.

Wednesday 5: Stairs and Prejudice

This is a tricky step because it raises before our eyes issues of Hobbit prejudice that were as delicate and sensitive then as they are today.

‘The Hill’ is a picture of Hobbit social stratification. The Shire of the late Third Age is hierarchical, and only the gentry live in luxurious top-of-the-hill holes, like Bag-end. But these are heads of families, not aristocrats, and Hobbit reproduction along with the relative scarcity of hills long ago prompted the Hobbits of the Shire to learn the art of building. To live in a house was common, even in the late Third Age, and a sign of neither poverty nor delinquency.

At the time the Red Book was composed, many Hobbits lived in houses, and some had stairs. Not all, to be sure – the house at Crickhollow does not, and I recall none at the Maggots. Yet some do, and more than one might care to mention, at least on the outside. Consider the reunion of Sam and Rosie.

Sam hurried to the house. By the large round door at the top of the steps from the wide yard stood Mrs. Cotton and Rosie, and Nibs in front of them grasping a hay-fork. (LotR VI, viii)

A Hobbit romance on stairs: Sam goes up them, Rosie sends him down and back to Frodo, only to run down herself to tell Sam to come straight back. Yet the Hobbit scribe situates the romance on ‘steps.’ A critical reader of the Red Book suspects retrospective gentrification.

As everyone knows, the Cottons and the Gamgees became the great families of early Fourth Age Hobbiton, but at the end of the Third Age the Cottons live in a house and the Gamgees had lived in a hole below Bag-end at the top of the Hill - a modest yet respectable hole with two windows, lending nuance to the social binary of hole-dwelling as described in the Prologue to the story of the War of the Ring:

Actually in the Shire in Bilbo’s days it was, as a rule, only the richest and the poorest Hobbits that maintained the old custom. The poorest went on living in burrows of the most primitive kind, mere holes indeed, with only one window or none…

The situation was more nuanced than this hole versus house contrast might suggest, and properly speaking one must distinguish between the steps outside a hobbit house and the ‘stairs’ that - one presumes - connect the two levels of a multi-story house (one must presume because internal staircases are discretely hidden by walls).

Though no consensus as yet exists, most Undertowers antiquarians hold that it was the internal stairs - not the house nor even the extended door-steps - that were deemed beyond the pale in the days of the Red Book. The house of the Cottons is above the level of the yard, which is only sensible in a farm. But what were other Hobbits doing adding second floors? Yet some did, as ‘The Hill’ illustrates - though there is no hint that the Cotton house has an internal staircase.

●◌◊□

Within Hobbit society in those distant days, we conjecture that this use and misuse was apprehended - that is to say, first borrowed from another free people of Middle-earth and then registered in our own words - in terms not of class but of the outside world.

Population pressure had long ago pushed Hobbits out of the desirable hilly regions of the Shire and into flatlands like the Marish – where a horizontal home requires walls and a roof. Hobbits, it is said in the Prologue to the Red Book, learned this art of building either from Elves or from Men, yet it is also noted that over long years their building had been “improved by devices, learned from Dwarves, or discovered by themselves.”

Now, what are devices that we might have learned from the Dwarves? We know of only two: hidden doors and stairs. As we know of no hidden doors in the Shire at that time, and indeed the very suggestion of hidden Hobbit doors is preposterous, we conclude that the Hobbit who composed this Prologue was discretely invoking stairs.

The very euphemism ‘Dwarvish devices’ speaks to the foreign air that still surrounded stairs in the Shire in the days of Bilbo and Frodo Baggins. Stairs were employed by some Hobbits in their building, but the art of stairs had not been domesticated, properly speaking.

□●◌◊

All Hobbits know that some Hobbits have stairs, and all Hobbits deem internal stairs foreign. Polite Hobbits do not mention the stairs of other Hobbits.

First Conclusion: The real deal with stairs is found only between the lines of the story told by the Hobbits who authored the Red Book.

Thursday Supplement: Cotton House

Hobbits, Farmer Cotton had stairs!

Discovered this morning by an assistant librarian who was seeking a plan of the stairs of Cirith Ungol, and so rummaging near the bottom of the great pile of papers that are the early drafts of the Red Book:

‘What Farmer Cotton down South Lane?’ said Frodo. ‘We’ll try it!’ … They knocked on the door, twice. Then slowly a window was opened just above and a head peered out.’ … ‘All right! But don’t shout,’ said the farmer. ‘I’m coming down.’ (Sauron Defeated 84-5)

And we found a drawing! These internal Cotton stairs were edited out of the final draft of the Red Book.1

1 Editorial note: see drawing 175 of Hammond & Scull’s J.R.R. Tolkien: Artist & Illustrator.

Second Turn: Manuscript Marish Conversation

Wednesday 6: Are We There Yet?

Hobbits, attend! From the archives of the Undertowers Library we report on an early draft by the author of the Red Book. Unexpectedly, the heir to Bilbo Baggins is Bingo Bolger-Baggins, and he sets off on an adventure with his two young friends, Odo and Frodo Took. In this story, stairs are not yet hidden. In fact, they are the subject of a Marish conversation.

Our three young Hobbit bachelors are walking in the flat lands to the east of Hobbiton, where the fenland has been drained by dikes. The Hobbits are in the vicinity of the home of Farmer Maggot.

Hobbits, hold tight to your pocket handkerchiefs and don’t forget that this is not the story that you know, but an earlier layer. Bingo not Frodo is the Baggins and heir of Bilbo. We will get to know Bingo better in the coming Wednesdays because he was considered in those days something of an expert on stairs (though that did not save him on Weathertop).

But these are Odo’s Wednesdays. A hobbit not from this part of the Shire, Odo asks his two friends of Farmer Maggot:

Does he live in a hole or a house?

We are reading an early Bag-end draft from the archive. The author is unknown, and has been named ‘the ghost hand.’ This Marish conversation on stairs frames conventional Hobbit wisdom of the day on stairs by way of the witty conversation of three innocent young Hobbits, who do not know what awaits them on the other side of the Hill. This framing is achieved by a three-fold process in which two flights of fancy pivot on an observation that brings stairs down to earth.

First is a long narratorial digression on the hole versus house distinction and the social history of Hobbit building (which ended up in the Prologue to the Red Book - see the first turn of this first staircase). The other flight of fancy is the real-live Hobbit conversation on stairs, analyzed in the following Wednesday steps. And as we pivot from one flight of fancy to another, an observation brings us down to earth:

But Odo was not thinking about hobbit-history. He merely wanted to know where to look for the farm. If Farmer Maggot had lived in a hole, there would have been rising ground somewhere near; but the land ahead looked perfectly flat. (Shadow 92)

Odo’s question is architectural, and so geographical. A hole requires a hill but this land is flat. If the farmer lives in a house, it may be nearby; a hole means a longer walk. Odo is not concerned with social distinction but spatial distance – he wants to know how far he has to walk.

Wednesday 7: The Trouble with Stairs

‘What a nuisance, if you want a handkerchief or something when you are downstairs, and find it upstairs,’ said Odo.

‘You could keep handkerchiefs downstairs, if you wished,’ said Frodo.

‘You could, but I don’t believe anybody does.’

(Return of the Shadow, p. 93)

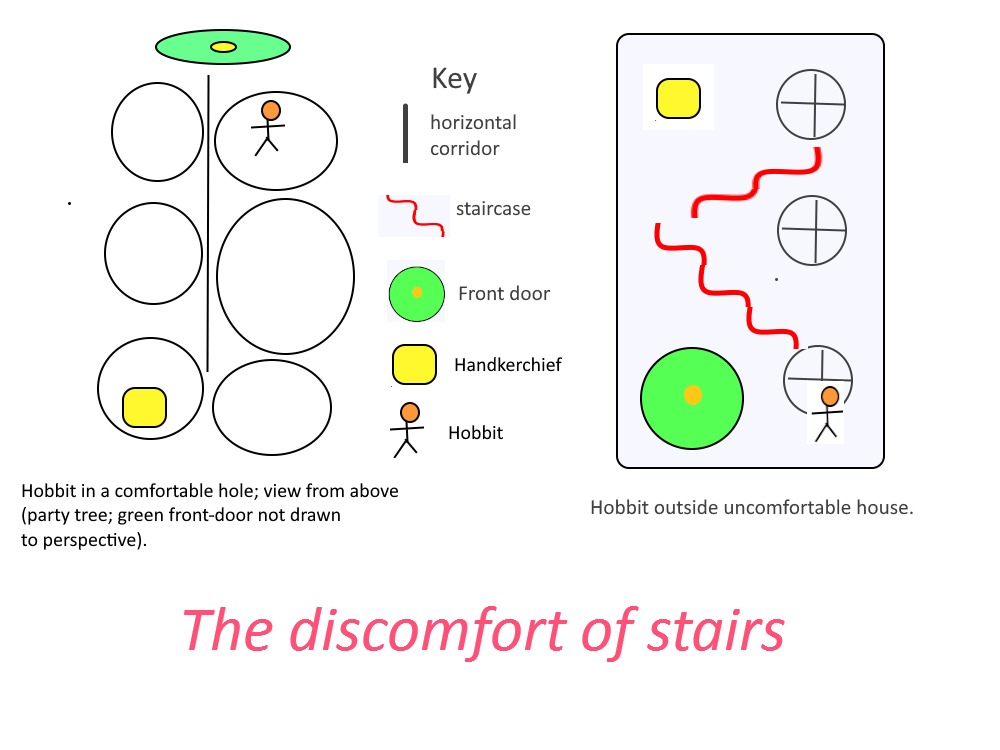

Wednesday 8: Diagramming the Nuisance

‘What a nuisance, if you want a handkerchief or something when you are downstairs, and find it upstairs,’ said Odo.

Odo goes to the very heart of the stair-issue confronted in this discussion, voicing an objection perhaps more far-reaching than you imagine. First, let’s look this Hobbit’s perspective on stairs in the face.

On the left is the control case, a stairless hole defined as comfortable. On the right the situation envisaged by Odo. In both cases Hobbit and handkerchief are in different rooms, but look carefully: for the Hobbits in the picture it is all the difference between a comfortable stroll and an uncomfortable climb. What a nuisance!

Wednesday 9: The Diagram Unveiled

‘Fancy climbing upstairs to bed!’ said Odo. ‘That seems to me most inconvenient. Hobbits aren’t birds.’ (Shadow, 92)

Almost we are back where we began, on Wednesday 1 – the canonical statement in the face of an Elvish flet that even Hobbits with stairs do not sleep upstairs. But we are in the early drafts of the story found in the Undertowers archive, and the architect of the Red Book had not yet worked out how to deal with stairs.

‘I don’t know,’ said Bingo. ‘It isn’t as bad as it sounds; though personally I never like looking out of upstairs windows, it makes me a bit giddy. There are some houses that have three stages, bedrooms above bedrooms. I slept in one once long ago on a holiday; the wind kept me awake all night.’

‘What a nuisance, if you want a handkerchief or something when you are downstairs, and find it upstairs,’ said Odo.

Hobbits talk nice, and gentle-Hobbits speak delicately (see last Wednesday 5). Odo’s HANDKERCHIEF veils a reality that may be upsetting to picture. The Guide to Stairs takes no pleasure in waving a magic wand and lifting Odo’s handkerchief. But Odo knows that Bingo and Frodo both know that a sleeve may do at a pinch. Odo’s OR SOMETHING allows the imagination to roam until, as it must, it encounters the element of time, raising the breathless prospect of a hurried climb or even a reckless fantasy of taking two stairs at a step. A handkerchief does not get cold and rubbery even as one navigates the sundering-stairway.

Wednesday 10: Bingo Bolger-Baggins, Stairmaster

Bingo Bolger-Baggins is a sort of mix of Sam and Frodo, more than each but less than both. He is a practical joker, who uses the magic ring for laughs. Bingo’s pranks include drinking a glass of beer while invisible in the house of Farmer Maggot and vanishing at his own birthday party at the beginning of his adventure. In this story, Bingo and not Bilbo is the host of the long-expected party!

The conversation in the Marish on which we are eavesdropping reveals Bingo a different Hobbit than was Bilbo at the start of his adventure. Bingo is already well-travelled and wise; though he has yet to climb an Elvish staircase.

Last Wednesday we heard Bingo describe “bedrooms above bedrooms” and a night on the third floor of a house on one of his holidays. Where was this holiday? Who can say? But Bingo now reveals he has been to the very borders of what was then the Shire, and maybe even beyond:

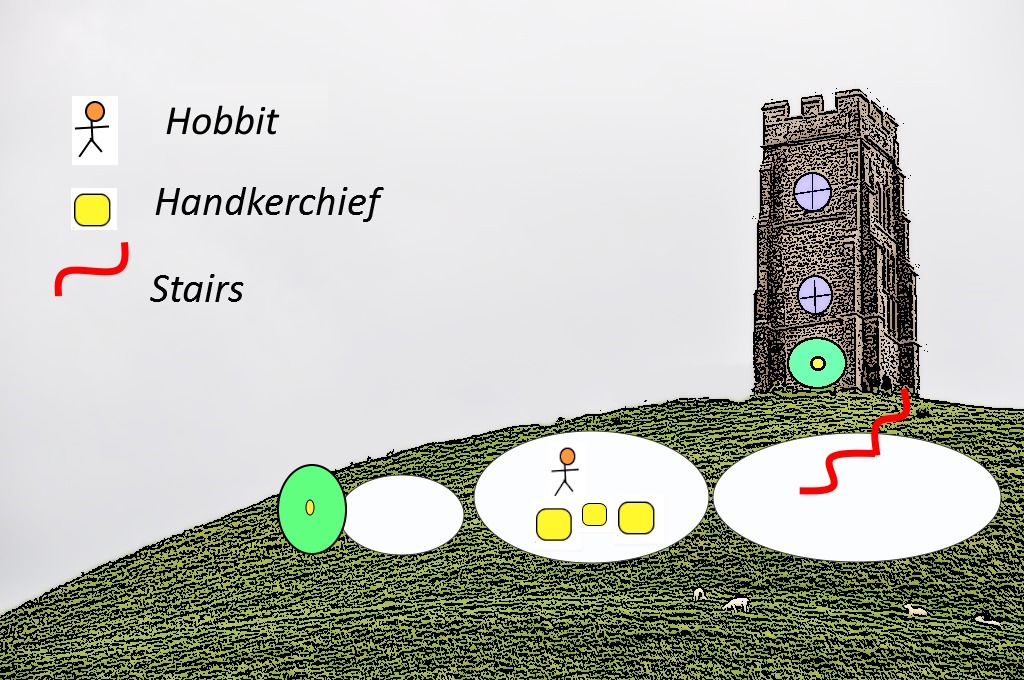

There used to be three elftowers standing in the land away west beyond the edge of the Shire. I saw them once. They shone white in the Moon. The tallest was furthest away, standing alone on a hill. It was told that you could see the sea from the top of the tower; but I don’t believe any hobbit has ever climbed it.

In the Red Book as we know it, our Elf-towers are revealed only in Prologue, dream, and appendix. Bingo has seen them. And he is also versed in the lore of stairs. Odo’s devastating criticism about pocket handkerchiefs kept upstairs generates the Profound Stair Lore of Bingo Bolger-Baggins:

The old tales tell that the Wise Elves used to build towers; and only went up their long stairs when they wished to sing or look out of the windows at the sky, or even perhaps the sea. They kept everything downstairs, or in deep halls dug beneath the feet of the towers. I have always fancied that the idea of building came largely from the Elves, though we use it differently. (Return of the Shadow, p. 93)

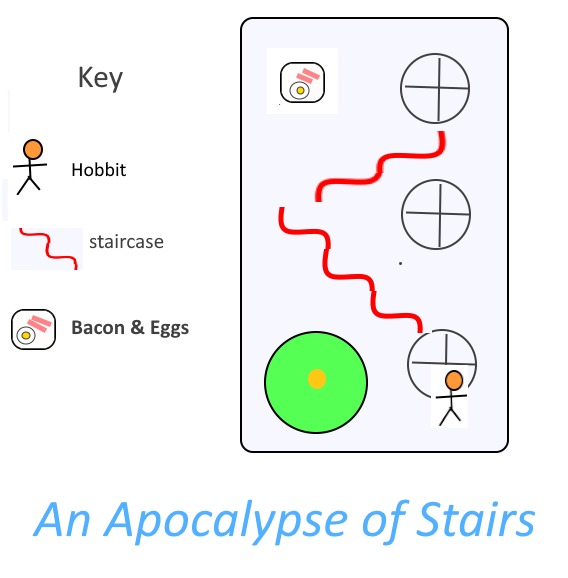

This image depicts the Elf-tower as Frodo and Odo imagine it from Bingo’s description. They know enough to picture the front door on the building rather than the edge of the underground holes, but suppose round doors and windows natural to all buildings in Middle-earth. But they know buildings are rectangular and so imagine an architectural babel.

In this picture the Elf is wisely selecting a handkerchief before ascending the stairs to look on the view. This image recalls the Folly on the Hobbiton Hill of our own day, but has not yet arrived at the heart of the Folly as, in contrast to the mock Elf-tower of our own Albusbalbus Chubb, the stairs in this late Third-Age fantasy of an Elf-tower actually continue all the way to the top of the tower.

Wednesday 11: Bingo’s Folly

We are about to learn why Bingo Bolger-Baggins did not author the Red Book, the ultimate guide to stairs. Hobbits like facts that they already know, set out squarely with no contradictions. Here are the facts:

- Bingo has been in houses with bedrooms above bedrooms and seen our 3 Elf-towers with his own eyes

- Bingo does not get stairs

We are facing Odo Took’s devastating ‘handerkerchief’ criticism (see last few Wednesdays). Frodo Took has pointed out that Hobbits could keep the ‘handerkerchiefs’ downstairs, which Odo does not deny - he merely points out that no Hobbit does.

‘That is not the houses’ fault,’ said Bingo; ‘it is just the silliness of the hobbits that live in them.’

And Bingo launches into his account of the Wise Elves and how they kept their stuff on the ground floor, or underground, and only went up the stairs to the top of their towers to sing, or to look at the stars or perhaps the sea (see last Wednesday). Bingo concludes:

If I ever live in a house, I shall keep everything I want downstairs, and only go up when I don’t want anything; or perhaps I shall have a cold supper upstairs in the dark on a starry night.

This image does not depict Bingo’s ideal of house-living but rather draws out on the level of Fantasy the contradiction in his mind, revealing why this is not the Hobbit who will write the great guide to stairs that is the Red Book. Hobbits, note the following facts:

- The tower on the hill is a pointless folly, as the windows of the hole in the Hill already provide a view!

- The door to the hole is a working door but the door to the tower is a facade, stuck on the stone because that is what the Hobbits of those days thought a tower is supposed to look like (see image last Wednesday).

- Talking nice and proper is all very well but the ‘handkerchiefs’ that place the raw facts behind a veil are liable to confuse the unwary listener and must be lifted on occasion (see Wednesday 10). A handkerchief may be placed in a Hobbit’s pocket, and as such is not equivalent to a plate of cold chicken, some pickles and a salad, and also some cheese, and a cake too, and of course beverages.

After a few weeks of usage the top floor of Bingo’s tower would be filled with spare cutlery, plates, jars of pickles, and, well, you can imagine…

Odo Took was right!!!

Wednesday 12: Foolish Hobbits

The adventure of Bilbo Baggins is told by a wonderful narrator, who knows just when to use a blanket and what to pull out of a pocket. The narratorial style of the later and longer part of the Red Book is quite different, and many deem its contents unsuitable for children.

The discovery of the Bag-end manuscripts in the Undertowers archive reveals the missing link between the two narratorial voices, and why it went missing. Already, this new tale is deeper and darker, but not yet because of the magic ring! The story that we are in is the original sequel to the adventure of Bilbo Baggins. As we all know, the wizard outed Bilbo’s Took quality by prodding him out of his own hole in the ground and into some others, such as the nasty wet hole of Gollum and the rather hotter hole occupied by Smaug. Now, the first heir of Bilbo Baggins is on an adventure closer to home and on his way to a hole on the other side of the Hill.

The party of Hobbits has walked down from the top of the Hobbiton Hill and is now trotting through fenland on the way to Buckland and then the realm of Tom Bombadil. The House at Crickhollow contains no stairs, but the House of Tom Bombadil does. Just as in the House of Beorn, blanket-over-head is the correct response on hearing nightly hoises. What is more, in a House in which we find Goldberry, the River-woman’s daughter, we should know also not to peek up these particular stairs.

Handling of this new story is delicate. Bilbo was one singular Hobbit, who adventured only in middle-age but is only a little Hobbit and so of particular appeal to children, and the grown-up Hobbits who read them stories. Readers both big and little alike know what is sensible blanket policy on hearing nightly noises, whatever side of the Misty Mountains be the House. But tweens of every age of the world do not.

The Marish conversation pokes fun at young gentle-Hobbits, whose wit sparkles in the fine air of abstraction as they walk into a marsh. As with lunch on the Barrow-downs, these Hobbits do not have their eyes open to the pertinent facts on the ground, nor do they have any inkling how a stairway may be used to leave the ground. But though we are on the road to the Barrow up on the Downs, we are still in the Shire, and the story is working a joke that may be opened up in relation to the untold story of Bag-end.

Bilbo and Frodo were exceptional as bachelors (Prologue), and we may wonder that Bungo Baggins and Belladona Took burrowed Bag-end but left in it but the one son, Bilbo. In the end, it takes Sam and Rosie Cotton to populate this Hobbit-hole as it was clearly designed to be used:

And also you have Rose, and Elanor; and Frodo-lad will come, and Rosie-lass, and Merry, and Goldilocks, and Pippin; and perhaps more that I cannot see. (LotR, VI, ix)

The reality of regular Hobbit life establishes what upstairs rooms in a house, as well as the spare rooms on the same level in this hole, will actually be used for. The bachelor fantasy of some Hobbit-snack whilst doing an Elvish-view from upstairs, and its exposure as a fantasy by Odo Took with his clever talk of handkerchiefs is - basically, fundamentally, and intentionally - foolish. These three Hobbits are genial and their conversation sparkles, but they are clueless tweens.

The scene is funny, but the gulf is too wide. Not even the art of the authors of the Red Book could make the conversation of tweens anything but annoying to everyone else. Wisely, the narrative apparatus was developed to meet the needs of the new story, eventually arriving at the Red Book as we know it.

But in this process the prejudices and different points of view that we climbed past on the first turn of this first staircase were absorbed into the unstated presuppositions and biases of the Bag-end authors. In the Red Book, stairs as stairs vanish as a polite subject of Hobbit conversation.

Third Turn: Hobbits burrow, wights borrow barrows

Wednesday 13: The Guide to Stairs

If you are a Hobbit – own it!

Bingo is right about how Elves use towers. If you are an Elf you already know this and don’t need a guide to stairs. And if you are a Dwarf, you know how to do stairs in a hole. But if you are a Hobbit you likely confuse the very different stair-lores of houses and holes, and even if you have the theory are liable to make an architectural mess in practice - and that is OK!

Hobbits are horizontal hole-dwellers. We find comfort in a corridor burrowed almost but not quite straight into the side of the Hill. From a domestic point of view, even the stairs of our own houses appear unnatural, or at least foreign. We turn our faces away from the Dwarvish devices common in the houses of our own valleys.

Nor are we wrong to turn our faces from stairs. Because the simple fact is, whichever way you look at them, stairs are a nuisance. But we all know that on some occasions stairs simply must be climbed, or be got over in one way or another. Some Hobbits do run off into the blue, and so learn about stairs the hard way (if you are one of these Hobbits you might consider writing for the Guide). But sensible Hobbits rightly prefer to read stories of other Hobbits who step up to the challenge of stairs.

Naturally, some young Hobbits experiment with stairs, even within the Shire. We at Undertowers have always been tolerant of Hobbit stair-use, so long as it remains on the ground. But every visitor to Hobbiton has seen the Folly on the Hill. We can no longer turn a blind-eye to stair-abuse in our own backyard. The overlooked tale of Bingo Bolger-Baggins in the Barrow provides our first Hobbit lesson on stairs:

Hobbits cannot attempt a stair if their foundation is the wrong sort of hole!

We infer that the Hobbiton Hobbits of the Late Third Age were already forgetting the meaning of their own barrows. This was not simply because they were building houses - they were also not using the holes in the tops of the Hills as they were designed to be used (see last Wednesday). Hence arose the story of poor Bingo Bolger-Baggins, who came to himself in a Barrow the better to recall the shape of his own burrow.1

1 Readers of the modern edition of the Guide have asked the question: ‘Does all the mess of our own day arise because those early 21st-century movies passed over the Barrow-downs?’ The answer, indubitably, is yes.

Wednesday 14: Barrow

Raising himself on one arm he looked, and saw now in the pale light that they were in a kind of passage which behind them turned a corner. Round the corner a long arm was groping, walking on its fingers towards Sam… (LotR, I, viii)

A Hobbit-hole at the top of a Hill looks for all the world like a barrow. At first glance, this stairless hole appears to be Bag-end in a mirror, the hole awaiting on the other side of the Hill. Hence, some Hobbits have worried that their burrow is quite the wrong kind of hole, being in fact a barrow, where the dead are housed.

Hobbits do not fear! Here are 3 simple tests to establish if your burrow is really a barrow:

- Shape of Windows and Door: No sign of round windows and door on the abode of a Barrow-wight.

- Roof decoration: Bag-end has a tree above it, while barrows have standing stones.

- Corners: The passage in a barrow is not a corridor going nearly straight into the side of the Hill; it has a corner.

Wednesday 15: Tomb raiding

- Question: May one borrow what a wight had borrowed in the barrow?

Answer: Yes, as Meriadoc Brandybuck demonstrated to the wraith-king of Angmar.

- Question: Can one take back what is now in a Hobbit’s burrow?

Answer: Not if he sets out on the road in time!

- Question: What is the difference between borrowing from a barrow and borrowing from a burrow?

Answer: If this is a polite way of asking about burglary, then the tricky turns in a Hobbit-hole in the Hill are the rooms on either side of the corridor, while the tricky turn in a Barrow on the Downs is the corridor itself, which may have a wight hanging around it.

Hobbit burglars, do not confuse burrow with barrow! Uninvited occupants are found in both, but the risk is much higher in a barrow. Roof decor may vary, so tree and standing stone are not sure guides, and if the roundness of door and windows is not sufficient sign, you must look out for the corridor.

A corridor with a corner is a sure sign that you have broken and entered into the wrong kind of hole.1

But remember Bingo Bolger-Baggins in the Barrow: real Hobbits don’t abandon their friends in bad holes!

1 Editorial note: Today we know more of the wrong kind of hole than did even the Hobbits of Undertowers. One sign that you are are in the wrong kind of British burrow is a corner, and another are doors that open from rooms into rooms. If you find yourself in either of these two kinds of hole, however snug and comfortable you may feel, your should get out while you still can! For a detailed antiquarian account see this older Library note. But here is the long and the round of the aboriginal remains on British Hilltops:

- Long Barrows are the older barrows of the British Isles. They were raised by the very first farmers, whose language is utterly forgotten. These barrows have long passageways or corridors cutting pretty straight into the side of the Hill.

- Round Barrows were built by those have been called the Beaker Folk, who introduced new things made by cunning hands, and did their death chambers very differently.

- A Hobbit-hole is the perfect synthesis of the two kinds of British Barrow: on the outside a Round Barrow, but characterized internally by a long passsage.

Wednesday 16: Out through the Window

In the dead night Bingo woke and heard noises: a sudden fear came over him… hooves seemed to come charging down the hillside from the east, up to the walls and round and round…

Tom looked at him. ‘Horsemen,’ he said… What ails the Barrow-wights to leave their old mounds? (Shadow 118-20)

From the archive of the Undertowers Library comes the revelation that the Black Riders that had already spooked Bingo and company in the Shire are, in the ‘ghost story’, Barrow-wights on horseback. Do Hobbits need further proof that the whole story of Bingo Bolger-Baggins in the Barrow was told as a warning to Hobbits that they have forgotten the meaning of their own holes?

But the remarkable finds in the Undertowers archive include much in addition to the massive pile of early drafts of the Red Book. One of the more deeply buried folders turned out to contain a collection of old Marish poems on Tom Bombadil. These Marish poems cast light upon the facial hairs seen on the Stoors, which appear to have once suggested the distant kinship of Maggot and Bombadil, who are glimpsed in the ‘ghost story’ as related aboriginal survivals of these two sides of the Hill (Shadow 117).

Of particular interest is the Marish tale of ‘The Adventures of Tom Bombadil’, which tells how Goldberry, Willowman, a family of badgers, and a Barrow-wight try to catch Bombadil, who escapes by the power of his voice, but returns to capture Goldberry as his bride.

The mystery of power is framed in the Marish poem, although one must lift the pocket handkerchief to see what is shown. Let us be clear on the editorial policy of the Undertowers Guide to Stairs: Our Hobbit authors are not permitted to consider opening the door of the original House of Beorn at night nor to head upstairs in the House of the sequel. Is it not enough to know that you may dream secure for tonight within these walls? After all, you will have to leave them soon enough. Do not be absurd, and maybe tomorrow it will rain.

But in this early Marish poem Bombadil begins a bachelor, and here it is permitted to follow the Barrow-wight upstairs in the House. Here we discover the curious fact that the Barrow-wight does not appear to do exactly as told.

Dark came under Hill. Tom, he lit a candle upstairs creaking went, turned the door-handle

‘Hoo! Tom Bombadil, I am waiting for you just here behind the door! I came up before you.’

‘Go out! Shut the door, and don’t slam it after! Take away gleaming eyes, take your hollow laughter!’

Out fled barrow wight through the window flying, through yard, over wall, up the hills a crying

(Editorial note: see The Adventures of Tom Bombadil for a post-Red Book reading and The Oxford Magazine for the original and for precise comparison ‘Peeling the Onion’, a rare surviving work of the predecessors of the Undertowers antiquarians.)

Wednesday 17: Aboriginal Stairs

Tom Bombadil is an ‘aborigine’ - he knew the land before men, before hobbits, before barrow-wights, yes before the necromancer - before the elves came to this quarter of the world. (Shadow 117)

Hobbits of Undertowers, attend! Our own Marish poems reveal how our Shire notion of the House of Tom Bombadil has been corrupted by the readings of the Red Book by the Big Folk of Gondor and elsewhere. Big Folk take Bombadil to be the riddle, and forget all else. But Bombadil is one with his aboriginal house and enchanted staircase, which Goldberry now also ascends and descends, and in which the Hobbits are merely guests on their way up the Downs to the Barrow.

The question that Hobbits should ask concerning the House of Bombadil is why, having pulled Tom into her River by his beard, Goldberry would consent, after Bombadil then caught her, to live in his House?

But the question that Hobbits should really ask is what the enchanted stairs of the House under Hill have to do with the burrow at home and the barrow ahead? Tom Bombadil indeed asks us all the riddle of our identity. But in our story he is asking the riddle of Hobbits, and so preparing us for what awaits up on the Downs.

What is about to be revealed to our Hobbits is the uncomfortable reality of a passage with a corner. But such is the way of the Red Book, and especially that part read in these very early drafts, that the passage from the right kind of hole to quite the wrong kind of hole is one of ever more dreamlike enchantment, so that the stairs at the heart of the Hill are liable to be overlooked by big and little readers alike.

Pondering the text with sober reflection, we learn that before Hobbits settled this land, there was Valley, River, fen, forest, up Hill and Downs. Always there was Tom Bombadil, his House, and within his walls an internal flight of stairs up to his bedroom.

So in passing through the House of Bombadil on the way from the burrow to the barrow, we glimpse the stairs that are aboriginal to our Hill, at least when it is seen from both sides.

Wednesday 18: Stairs no Nightmare

Stairs are not natural to Hobbits. Our nature is born from the long passage or corridor that we burrow nearly but not quite straight into the side of the top of a Hill.

Stairs are used by some Hobbits who build houses. Yet to this day they appear foreign, Dwarvish devices, which gentle-Hobbits might talk about in private, but not in the pages of the Red Book.

But stairs, though they invoke a dream of Dwarves, or Elves, or something else besides, are no nightmare.

A corner in a passage is a nightmare.

Stairs are no nightmare. Stairs are foreign, but useful in flat places, and absolutely vital in special cases, such as a good Hobbit story. Stairs work a Hobbit’s enchantment. And in our story of hole-dwellers under Hill, stairs are aboriginal.

Stairs were at the heart of the Hill before Hobbits burrowed or Big Folk barrowed. Before the first rain drop and the first acorn fell a stairway was ascended and descended. These stairs will remain at the heart of the Hill after the last Hobbits have vanished from their holes and the last wight is reuinited with the darkness that has returned from Outside.

Staircase to Second Floor: Hill of Doom

Wednesday 1: First View from Bree

Our Hobbit scribes are taking a breather. Hobbit readers should too!