‘Seeing Stones’ is an ongoing series about a short story told by J.R.R. Tolkien one Wednesday in 1936 and subsequently worked up into a long story about the Ring of Sauron. Following Tolkien’s Beowulf criticism, this series unveils the design of The Lord of the Rings to restore a sense of history to Middle-earth.

‘Seeing Stones’ turns our reading of Tolkien inside-out. Looking forward, we discover how the germs of a fairy-story, fashioned of metaphors and told as an allegory in an academic lecture, shaped the Third Age of Middle-earth. Turning around, and reading The Lord of the Rings as commentary on the 1936 allegory of Beowulf, we recognize that this long story is Tolkien’s Beowulf criticism, though it has never before been read as such.

The series is hosted on the Silmarillion Writers Guild, as part of the newsletter column A Sense of History. A new post is published each month and linked from this page.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Allegory in Old Stone

Tolkien’s Friends

Elostirion

Critical Turn

- Passing Ships

- On the Shape of the World

- A Legend of Beleriand

- Tower, 1936

A New Rock Garden

- The Other Side of the Hill

- Bridge

- Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age

- Round World

A Sense of History

- Review

- Fairy-tale Turn

- Staircase

Epilogue. Undertowers

Introduction

Below a coin-bright moon, a corkscrew spine turns, and turns again. The serpent bites down - too late!

Allegory in Old Stone

- We begin in London in 1936 as J.R.R. Tolkien defends the art of the Anglo-Saxon author of Beowulf in a lecture at the British Academy. Three posts frame the famous allegory of the tower against the context of the times, the argument of the lecture, and an earlier image of the poem as a rock garden.

1. One Wednesday in 1936

Tolkien’s famous British Academy lecture ‘Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics’ was delivered in November 1936. A shadow was then falling over Europe. We begin with a reading of the ‘northern theory of courage’ invoked in the lecture in relation to the view from the high windows of England’s ivory towers. Comparing Tolkien’s lecture with The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money of John Maynard Keynes, published earlier in the year, reveals a contemporary academic fixation with Time and a careful reappraisal of the place of imagination in the making of history.

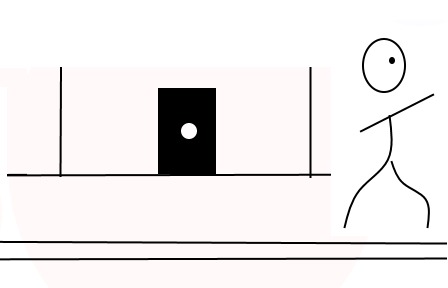

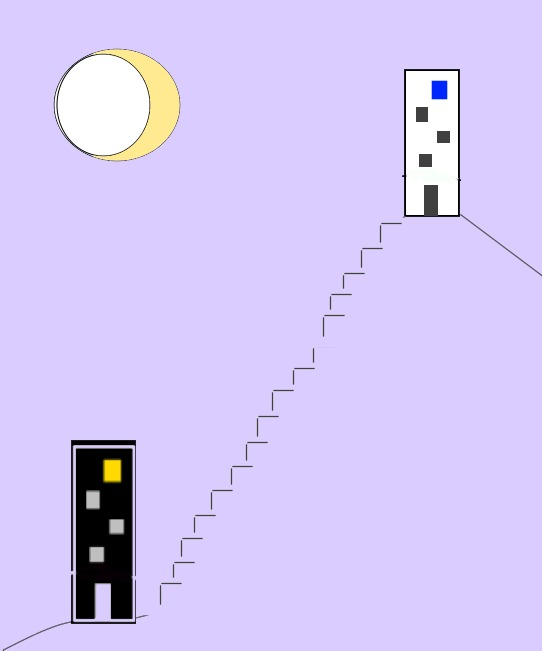

2. Anglo-Saxon Tower

The 1936 allegory of the tower is read in the context of the lecture in which it was delivered, revealing an Anglo-Saxon time machine. Beowulf is a tale of a heathen hero of the old homelands of the Angles and other tribes before their settlement in the British Isles and conversion to Christianity. Tolkien pictures an Anglo-Saxon poet building an enchanted tower, the winding stairs of which lead from the green grass of a little kingdom in the British Isles to a view that had vanished from the Anglo-Saxon waking world. The old poet has pictured the ancient heathen world as one that knew of God, but not of heaven, and is in the process of forgetting what is beyond the horizon of the western ocean.

3. Rock Garden

The allegory of the tower began in 1933 as an allegory of a rock garden made with the old stones and commonplace flowers. In marked contrast to the allegory of the tower, which nobody appears to understand, the original allegory has the merit of providing a diagram of the poem that illustrates the argument of ‘Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics’. The point of contention is not the value of this over that stone, but the aesthetic value of the whole design. Tolkien argues that historical stones on the circumference and mythical stones in the center constitutes a difficult, ambitious, yet coherent design. The metaphor of the rock garden provides a way to think about Tolkien’s own stories, and invites the question why such a useful image was substituted for an enigmatic tower with a view, comprehension of which has defied even careful readers of The Lord of the Rings.

Tolkien’s Friends

- The 1936 allegory depicts foolish friends of the Anglo-Saxon author who demolish his tower. One fascinating dimension of this allegory is the way that Tolkien’s own friends have taken on the work of demolition in our own times. Three posts explore what I call the new-Elizabethan consensus on the allegory of the tower, curiously co-fashioned forty years ago by two warring academics.

4. First Brick in the Wall

With this post I open up the question of how for four decades we (Tolkien fans) have been content with the wrong reading of the 1936 allegory of the tower. Jane Chance Nitzsche (1979) was the architect of the new-Elbethan consensus - I mean the conventional reading of the 1936 allegory dropped on your head in online Tolkien forums since before even there was an Internet. This in itself is odd, because the thesis of Chance’s psychoanalysis of Tolkien’s ‘Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics’ is totally out to lunch. Chance it was who first banished the Historians from respectable Tolkien society. Unlike Tom Shippey, however, who will soon establish as dogma that the 1936 tale of a tower is just allegory, Chance glimpses the power of a fantastic story. The fantasy she unveils is her own, but read as fan-fiction we feel it touch the magic of Tolkien’s 1936 short story.

5. Fawlty Towers

Some years ago, Tom Shippey’s Road to Middle-earth (1982) awakened my interest in Tolkien’s philological studies. On reading this post, the emeritus professor called me an ‘online troll’. Surveying Shippey’s accounts of Tolkien and the Beowulf-poet, the post registers a protest against coyness in the face of evil. Reading ‘Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics’, Shippey points to some hallmarks of Nazi ideology but declines to unpack what he is hinting at. Like Chance, Shippey is uncomfortable with the ‘descendants’ of the allegory, and vanishes them. With this Shippey completes the restructuring of Tolkien’s story begun by Chance. In this modern adaptation of the allegory, the two distinct groups of ‘friends’ and ‘descendants’ are evaporated and replaced by one group of destructive Critics, who turn out to be Historians.

- Written before but published a few days after October 7, 2023, reception of this post was surreal. Receiving the news on the ground here in Israel and looking murderous antisemitism in the face, I was at the same time receiving also a stream of messages from friends abroad, genuinely concerned not for the safety of my family but rather my good name in light of the series of nasty comments accumalating under Shippey’s (since deleted) rebuttal on his academia.edu page. What can I say? Footnote 4 of the following post takes apart Shippey’s botched analysis of the 1936 allegory. For an SWG perspective on this illustration of what ‘Tolkien scholars’ do in the dark, see here.

6. The Peaks of Taniquetil

Early in 1936 Tolkien composed ‘The Fall of Númenor’, which told how the flat world became a round sphere. Some people in the newly round world build high towers to better look out on the old ‘straight-road’ over the sea. These Númenórean towers become the three Elf-towers of Emyn Beraid on the margin of The Lord of the Rings. Back in 1982 Shippey remarked on the similarity of Elf-towers and the tower of the 1936 allegory, but declined to investigate a ‘private’ image of a ‘non-scholarly’ literary desire. Taking a hint, Seeing Stones now steps out of 1936 and into 1967, when one could purchase in a bookshop all three volumes of The Lord of the Rings, and also an obscure volume of songs from the Red Book set to music, The Road Goes Ever On.

Elostirion

- Four posts on Elostirion, the Elf-tower on the western margin of The Lord of the Rings. When we bring this Elf-tower into focus, the map of the story is enlarged while hidden narrative threads are revealed. Together, these posts point to Elostirion as central to the design of The Lord of the Rings. Only on concluding their composition did I understand that they had been written in dialogue with Verlyn Flieger’s A Question of Time (1997), which taught me how to read the enchantment of Tolkien’s story but overlooks Elostirion as a source of enchantment.

7. In the House of the Fairbairns

Both Anglo-Saxon tower and Elf-tower are enigmatic, but careful reading unearths more on the Elf-tower. This post proposes a solution to a literary riddle, posed in the long ago by my friend Tom Hillman: How is the vision of Valinor beheld at his end by Frodo Baggins recorded in the Red Book of Westmarch? I propose an answer by way of two of Frodo Baggins’ far-seeings: in the house at Crickhollow and on his second night in the house of Tom Bombadil, which point to, respectively, the Elf-tower and the Seeing Stone or palantír within it.

8. Seeing Stones in Dark Towers

This post completes my investigation of the three far-seeings that follow the night that Frodo spends with the Elves in the Woody End. Between two intimations of a view of Valinor, the intermediary dream, the first in the house of Bombadil, takes us inland to Orthanc. As inscribed above the western doors of the Mines of Moria, that magical illustration of Elf-Dwarf collaboration, the name of the game is treachery. Stepping from Orthanc to two towers on the border of Mordor, I suggest that Tolkien has drawn in the person of Frodo Baggins the image of the Stone by which the will of the Necromancer enters a Tower.

9. Crossroads

The Road Goes Ever On (1967), a late work of J.R.R. Tolkien, includes annotated translations of two Elvish songs, Namárië and A Elbereth Gilthoniel. This post reads in these two commentaries the hand of Tolkien drawing aside a veil to disclose Elbereth on the mountain beyond the Sea, watching over the journey of Frodo Baggins. This image is hidden in the Red Book, but Tolkien hints that it had been received by Gildor Inglorion and the Elves that Frodo, Sam, and Pippin meet in the Shire. This first crossroads of the narrative offers an explanation of Frodo’s three far-seeing visions. Looking back from the crossroads to the Stone in the Elf-tower, we now have a notion what the Elves saw in it.

10. Thálatta! Thálatta!

The encounter of Frodo Baggins and the Lady Galadriel, the keystone of The Lord of the Rings, draws a semblance of the hidden image received in the Stone in the Elf-tower. While he never in waking life climbs the stairs of this tower, in Lothlórien Frodo Baggins descends a flight of steps to look into Galadriel’s Mirror, wherein he first sees the sea. Analysis of the two ships that Frodo sees on the sea reveals Tolkien’s conception of a Third Age of Middle-earth, a last age of our world when the light of the Valar might still be seen, though it was hidden to mortals.

Critical Turn

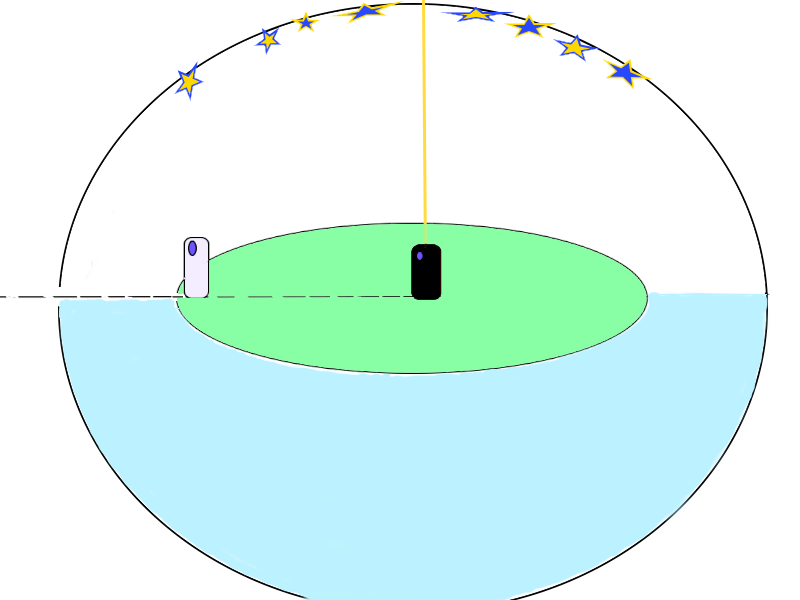

- Having observed in January that Elostirion was first imagined as built by the exiles of Númenor, we step back to 1936 to delineate the relationship between Númenórean and Anglo-Saxon towers. Four posts spell out the fundamental claim of Seeing Stones: ‘The Fall of Númenor’ gives the key to the allegorical tower of ‘Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics’. Read right, the allegory is in turn the key to Tolkien’s Beowulf criticism, illustrated above. Tolkien’s critical picture frames the flat world of ancient northern myth within the circle of a Ptolemaic model of the cosmos, juxtaposing in one composite picture the two perspectives on the world of an Anglo-Saxon who ascends to the top of this enchanted staircase.

11. Passing Ships

A return to 1936, to look with Tolkien into the exordium to Beowulf, wherein are seen two ships sailing on the sea. The first sails to our shores out of an ancient myth of the coming of the king. The second ship is an innovation of the Anglo-Saxon poet, borrowed from contemporary British tales of the death of Arthur, and returns the body of the dead king into the Unknown beyond the horizon. Our challenge in the remaining posts of this first volume of Seeing Stones is to tease out the nature of the relationship between these two ships of the Old English poem and the three ships seen by Frodo in the Mirror of Galadriel; but to do this we must first get square on Tolkien’s Beowulf criticism.

12. On the Shape of the World

‘Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics’ criticizes the critics from the perspective of correct criticism, which draws the design of the Old English poem. This picture of Fusion (above) draws the flat-world of heathen mythology within the circle of the cosmos. This post considers the circle, which derives from the pagan science of ancient Greece and frames a division between Time (within the circle) and Eternity (outside): On a picture of a circle, an Anglo-Saxon of the age of Bede could draw the passage of the soul after death (the gold line). The heathen heroes of the poem may imagine themselves gazing out to sea from the shores of a round world, but Anglo-Saxon poet and audience know that they stand on a round world at the unmoving center of a round universe.

13. A Legend of Beleriand

A ship-burial suggests that beyond the Shoreless Sea is hell, the realm of mortal shades. Tolkien reads the first ship of the exordium to Beowulf as ancient myth, the ship-burial as Anglo-Saxon art. The art breathes meaning into the myth, yet raises the uncomfortable thought that the good king came to his people out of death. Early in 1936, Tolkien penned an Elvish myth that explained how Elendil sailed the straight-road, out of a mythical flat world and into the round world of hisory, and then died side by side with an Elf, fighting Sauron in Mordor. With this myth of the coming of the king from out of the sea, Tolkien spelled out his reading of the two ships in the exordium to Beowulf: the funeral-ship seems to return into myth but the straight-road is lost and this second passage becomes a metaphor for the passing of the soul out of the round cosmos in Time.

14. Tower, 1936

This post situates the Anglo-Saxon tower in relation to ‘Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics’ and ‘The Fall of Númenor’, revealing how Tolkien’s scholarship and fantasy met and kissed in 1936, with pregnant results. The story told here is how the rock garden that pictured the 1904 criticism of W.P. Ker became Middle-earth surrounded by the Shoreless Sea, so that Beowulf was redrawn as a tower. The transformation comes as Tolkien holds up Ker’s reading of ‘northern courage’ out of the Icelandic myth of Ragnarök, and draws Beowulf as an earlier, godless version of the same mythical apprehension of Doom. The ‘Last Alliance between Elves and Men’ on which concludes the myth of Númenor, maps the straight-road of this ancient English image of Ragnarök. The heathen heroes in the days of Beowulf know in their hearts that the straight-road is now lost, but the tower that the poet builds that looks out on the sea recalls the same battle in earlier, mythical ages of the world.

A New Rock Garden

- A return to the Elf-tower on the western margin of The Lord of the Rings, now read through a history of composition. These last two sections of the series iron out both the similarities and the differences between the Anglo-Saxon tower of 1936 and the Elf-tower on the margin of the story of Frodo Baggins. The next four posts observe how the Elf-tower was early set down in the narrative of the new Hobbit story and trace how over 14 long years of writing it was worked up and polished to become the hidden symbol of the design of the story discovered in posts 7-10 above on Elostirion.

15. The Other Side of the Hill

The drafts of The Lord of the Rings penned in 1938, the first year of composition, evidence a design for ‘a new Hobbit story’ of around the same length as the original, but with most of the action set off-road and before - rather than after - Rivendell. The germ was an idea that a party of Hobbits might enter the enchanted realm of the 1934 poem, ‘The Adventures of Tom Bombadil’. Against this background, the post considers why, as he walks on the flatlands of the Marish, Bingo Bolger-Baggins, the original heir of Bilbo Baggins, tells his friends of three Elf-towers that he once saw in the light of the moon, beyond the western borders of the Shire.

16. Bridge

Before autumn of 1938 Tolkien considered the Black Riders encountered by the Hobbits in the woods of the Shire to be Barrow-wights on horseback. On Weathertop, a Hobbit confronted by the Ringwraiths put on the magic ring and saw their invisible faces. For the first time, Tolkien pictured the One Ring as a bridge between the visible world in history and the invisible realm of myth. The post explains this new conception of the magic ring as a dark and twisted mirror of the Straight-road, which was imagined as passing not over the sea but all the way to the Dark Tower of the Necromancer at the center of a new rock garden.

17. Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age

The map of the Third Age was drawn as Tolkien wrote into his narrative first Towers and then Stones. Reading the early drafts of The Lord of the Rings reveals the path by which the last part of ‘The Fall of Númenor’, which tells of the exiles of Myth who have fallen into History, was developed into ‘Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age’ (circa 1948), published in The Silmarillion. In this post we discover that the symbol of the Elf-tower with the Stone of Elendil was only introduced into the appendices once the narrative was completed.

18. Round World

By November 1944, Frodo was imprisoned in the topmost chamber of the tower of Cirith Ungol, and only in early 1948 did Tolkien write of Sam’s heroic ascent by stair and ladder to rescue his master. During this long break from composition, and in the wake of the end of a six-year war, Tolkien penned ‘The Drowning of Anadûnê’, a round world version of ‘The Fall of Númenor’. Why?

A Sense of History

- The series concludes with a comparison of the Anglo-Saxon tower and Elostirion. The result pinpoints the errors of the new-Elizabethan consensus, and corrects them to build on the insights supplied four decades ago by Verlyn Flieger, the greatest of the early pioneers of Tolkien scholarship.

19. Review

Jane Chance (1979) raised the key question about Tolkien’s art in relation to his scholarship. This question concerns The Lord of the Rings yet is posed by the historicity of Tolkien’s Beowulf. As a critic, Tolkien explains how the art of the Anglo-Saxon poet depended upon various local conditions that have now vanished - this staircase is not going to work for us today. So Tolkien was prompted to ask how an audience of his own day might be taken up the stairs of a tower. Chance opened the door to this question, but Tom Shippey closed it with his devastating 1980 review of Chance’s monograph. We approach the conclusion of this series by opening the door once again.

20. Fairy-tale Turn

With the return of Aragorn as king of Gondor drawn out of the exordium to Beowulf the critical theory of ‘Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics’ meets up with ‘On Fairy-stories’. The two final posts of this first volume engage with Flieger’s passage between Tolkien’s two great essays. My aim is to strip away the blending of two false readings (Chance and Shippey) that Flieger unfortunately bequeathed to posterity, replace it with a right reading of the 1936 allegory, and thereby unlock the potency of the original insights that Flieger brings to the relationship between these two essays.

21. Staircase

Returning once again to the exordium to Beowulf, the relationship between the Anglo-Saxon and the Elf-tower is delineated. In this post the heathen heroes under heaven who appear in line 52 of Beowulf are joined by three Hobbits, all gazing out to Sea at the ‘funeral-ship’ of the Bagginses. Once we agree what we are looking at here, we can all descend the staircase and return back to our own houses, wiser Hobbits, if not happier.

Epilogue. Undertowers

dracon ēc scufun, wyrm ofer weallclif, lēton wēg niman, flōd fæðmian frætwa hyrde.

Emyn Beraid was a place to climb a tower and look into a Stone and out upon the sea but the Tower Hills became a place to sit by the fire and listen to a book read aloud and gaze inland with the eye of the mind. In ordinary, everyday life the Hobbits of the Westmarch did not climb the towers on the Hill, but sometimes they did because they liked to look on the sea. Some even built boats and sailed out to sea, seeking a lost point of view.

Turn, and turn again.

Volume II. 1. Freawaru the Hapless

Volume II returns to 1936 and reads concurrently ‘The Fall of Númenor’ and Tolkien’s wider commentaries on the mysterious depths of the stones of Beowulf. We begin with the forgotten tragedy of doomed love and world-ending in the prehistory of Old English literature, the tale of the Danish princess and the last priest-king of the North. Echoes of the Entwives and the air of Númenor.

Art credits: Rock garden image worked up with thanks from Dave World’s The Callanish Stones 4k drone, Isle of Lewis, Scotland.